I am fortunate to have inherited 3 separate medical archives, and have collected more associated portraits and papers over the years relating to three of my ancestors. I have grown up around these portraits and papers, there is so much that resonates in modern times.

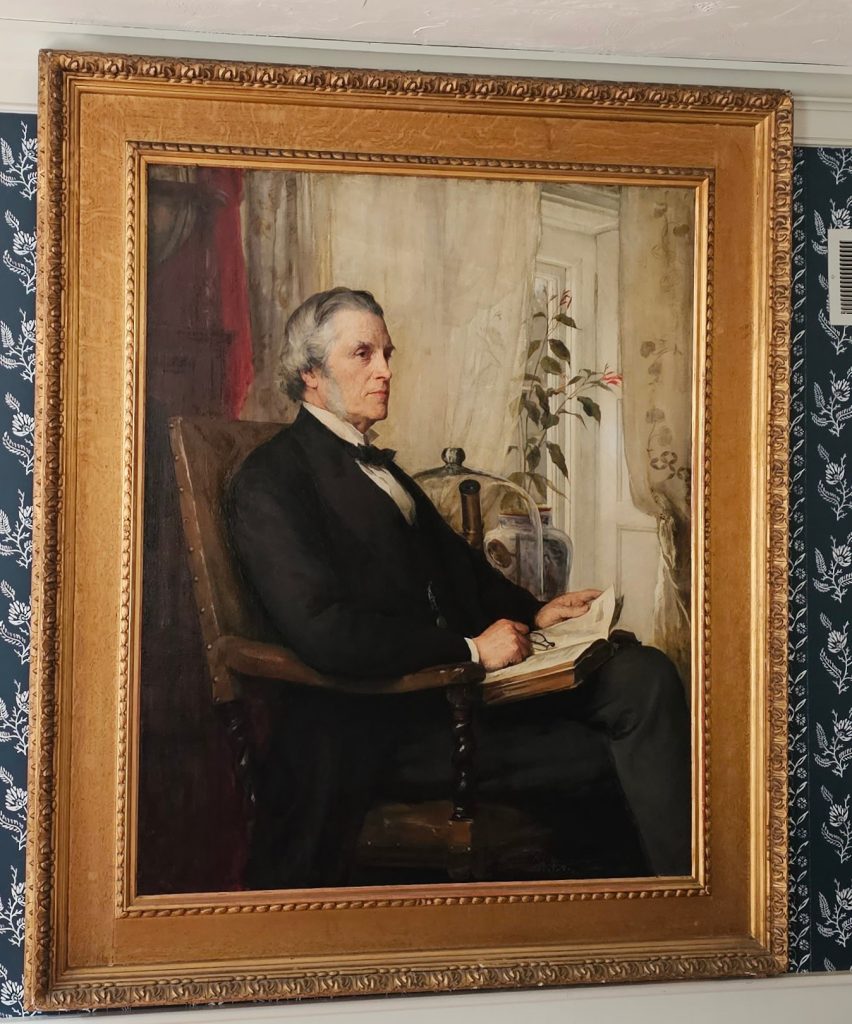

Sir William Bowman Bt. (1816-1892)

Sir William Bowman significantly impacted anatomical studies by connecting microscopic structures with their functions, focusing particularly on the kidneys, eyes, and liver. At the young age of 21, he joined King’s College London’s medical department, and subsequently became a surgeon at its newly established teaching hospital. Remarkably, by age 25, he was honored as a Fellow of the Royal Society. In 1848, he was appointed as a joint professor of physiology and general anatomy at King’s College Hospital alongside Robert Bentley Todd, maintaining ties with the institution throughout his life.

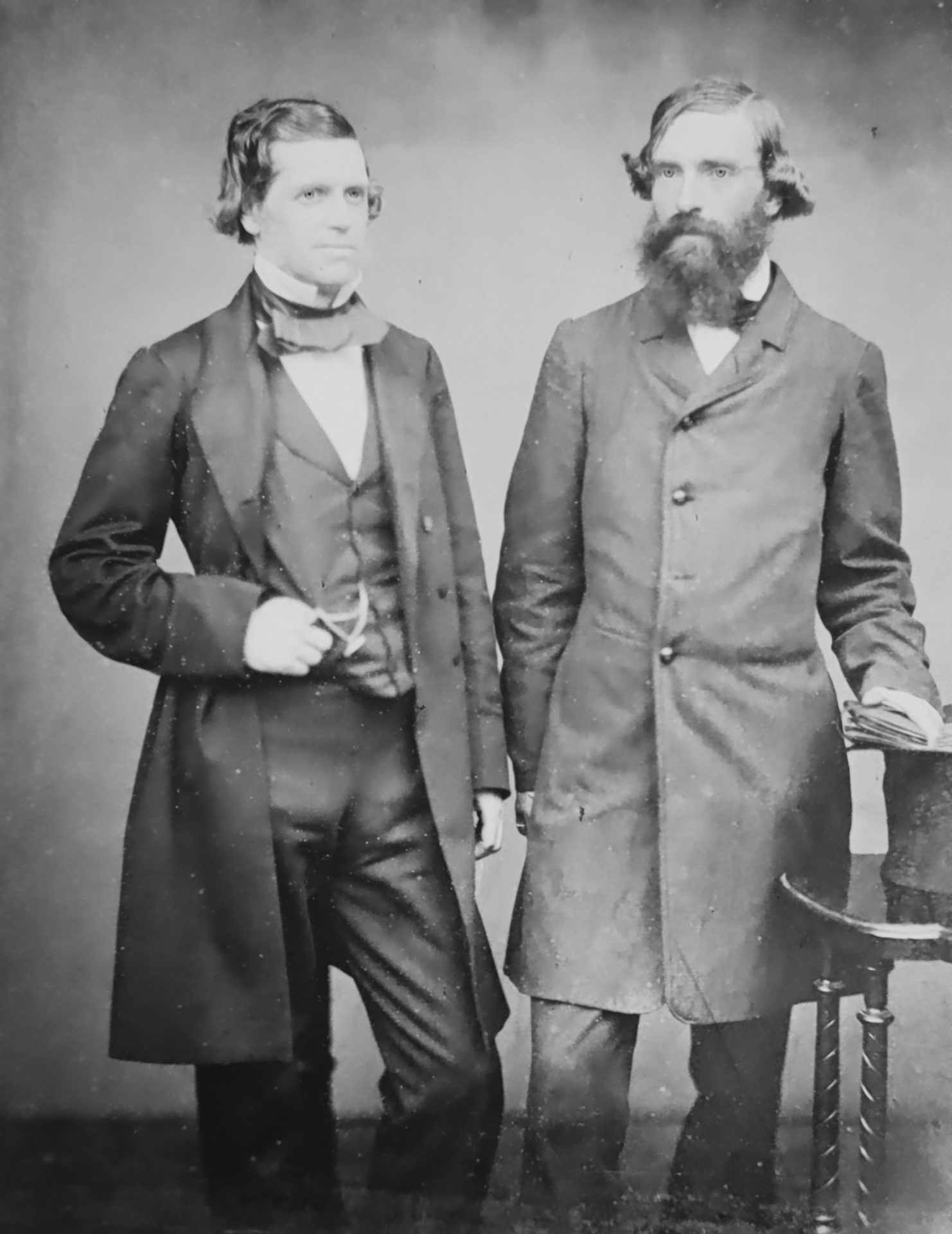

Bowman’s early career was dedicated to anatomical research, which peaked with his collaboration with Bentley Todd on “The Physiological Anatomy and Physiology of Man,” published between 1845-56. Post-1850, he shifted his focus to become a pioneering ophthalmic surgeon in England, particularly noted for his expertise with the ophthalmoscope. He was instrumental in founding the Ophthalmological Society of the United Kingdom and served as its first president. He maintained close ties with Albrecht von Graefe in Berlin.

Bowman and Von Graefe

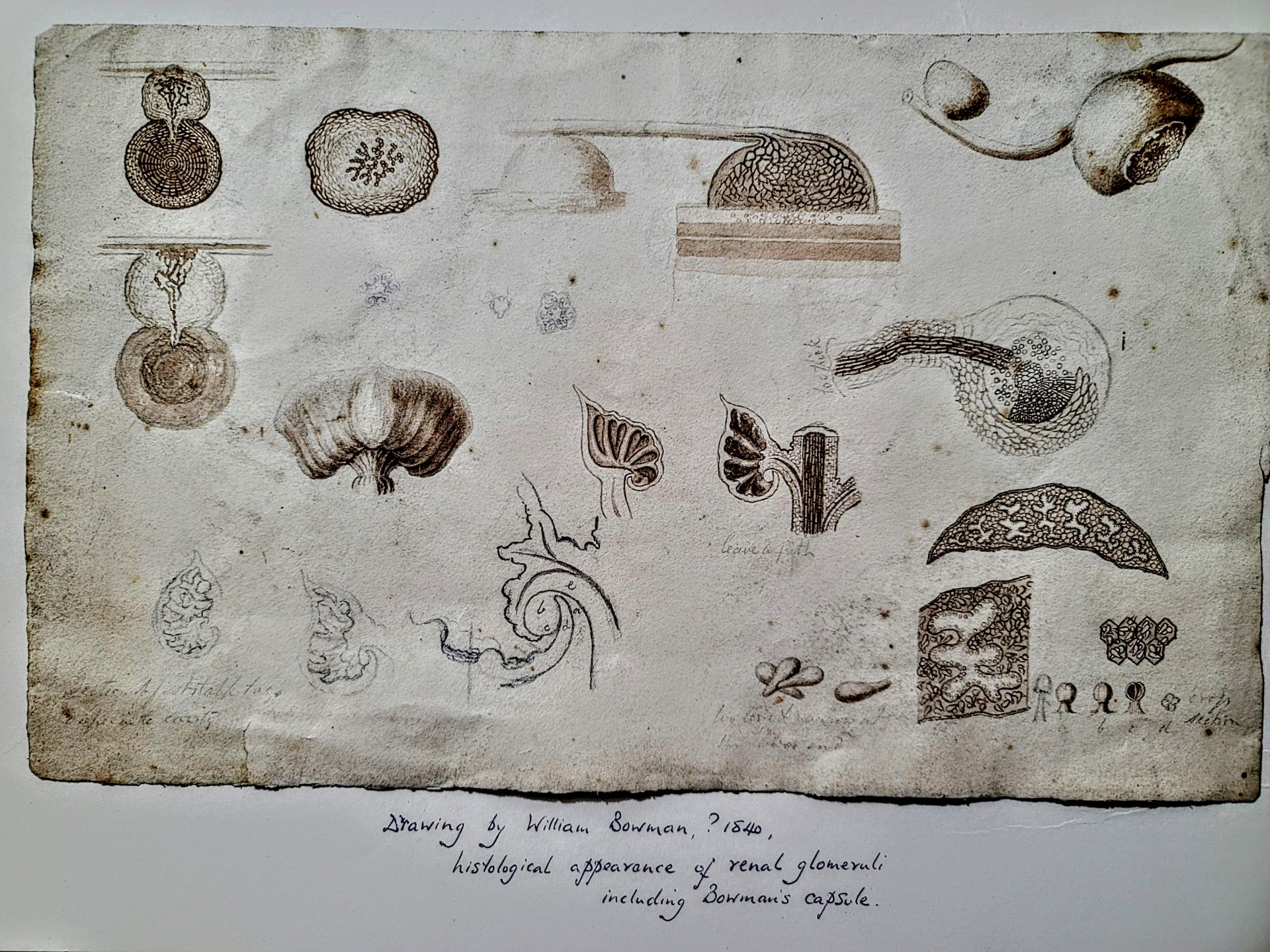

Beyond his medical achievements, Bowman was a friend to Florence Nightingale and contributed to healthcare by helping establish St John’s House and Sisterhood, aimed at providing trained nursing for the needy. His legacy in medicine includes naming several anatomical structures after him, such as Bowman’s capsule in the kidney, Bowman’s glands in the olfactory mucosa, and Bowman’s membrane in the cornea

.

This extensive archive contains letters from Florence Nightingale, a deep family archive of letters from his fathers family dating back to the late 1600s , and his own drawings of the Renal Glomerulus and Bowman’s capsule.

Sir William Arbuthnot Lane Bt. (1856-1943)

William Lane was born a Scotsman in Fort William, the son of a Military Surgeon. In a late Victorian world of authoritarian opinion driven surgical practice in Britain, Lane was calmly oppositional and defiant, but spoke with a quiet voice.

Sterile technique and the operative treatment of fractures

Initially he evolved towards the Asepsis movement coming out of Germany, in counter culture to Listerian Antiseptic dogma. This alone must have taken courage, but he went on to demonstrate what is probably the best evidence we have for sterile technique, by implanting hundred of orthopedic plates from 1895. Because he did not initially have gloves, he developed long handled instruments and coined the term “the no touch technique”. The British medical Association accused him of dangerous practice, but on investigation , in the age before antibiotics, they found no infections. Although Lane was the first to develop orthopedic plates and screws, it is for his institution of Apsepsis in Guys Hospital London that he probably best remembered for. Lane travelled often to the US, including the Mayo clinic and new York, proselytizing his operative treatment of fractures.

He was also able to master cleft palate repairs in infants at Great Ormond Street Hospital. It was from there that we have been donated his portrait in 2023

o

William Arbuthnot Lane, Hung in Great Ormond’s Street

Lane had the courage to be wrong as well, and was famously corrected for his views on large bowel resection to cure “autointoxication, in 1913 at the Royal Society of Medicine.

Birth of Plastic Surgery

During World War I, Lane served as an officer in the Royal Army Medical Corps, where he ascended to the position of head of army surgery. His significant contributions included his role as a consulting surgeon at Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot. Moreover, Lane was instrumental in establishing Queen Mary’s Hospital in Sidcup. Despite initial government reluctance regarding funding, Lane managed to allocate a ward to Harold Gillies at this hospital, providing the space where Gillies would go on to pioneer groundbreaking reconstructive surgery techniques. Patrick Clarkson was greatly inspired by his legendary reputation during his training at Guy’s hospital in the ’30s, perhaps so much so that he followed Harold Gillies into Plastic Surgery and and he married Barbara Mutch, Lane’s grand daughter.

Despite the prewar autointoxication setback Lane continued his concerns about chronic constipation, now as a cause for cancer, which lead him into potential conflict with the British Medical Association, again. He retired from medical practice and surrendered his General medical Council Registration to liberate him to talk directly to the public through advertising. He founded The New Health Society”, and advocated for fresh vegetables, female hygiene and very progressive issues including sexuality and transsexualisms.

The Lane archive house his hand corrected typed autobiography, portraits, his books, his walking cane, numerous letters from patients and colleagues and volumes from the New Health Society.

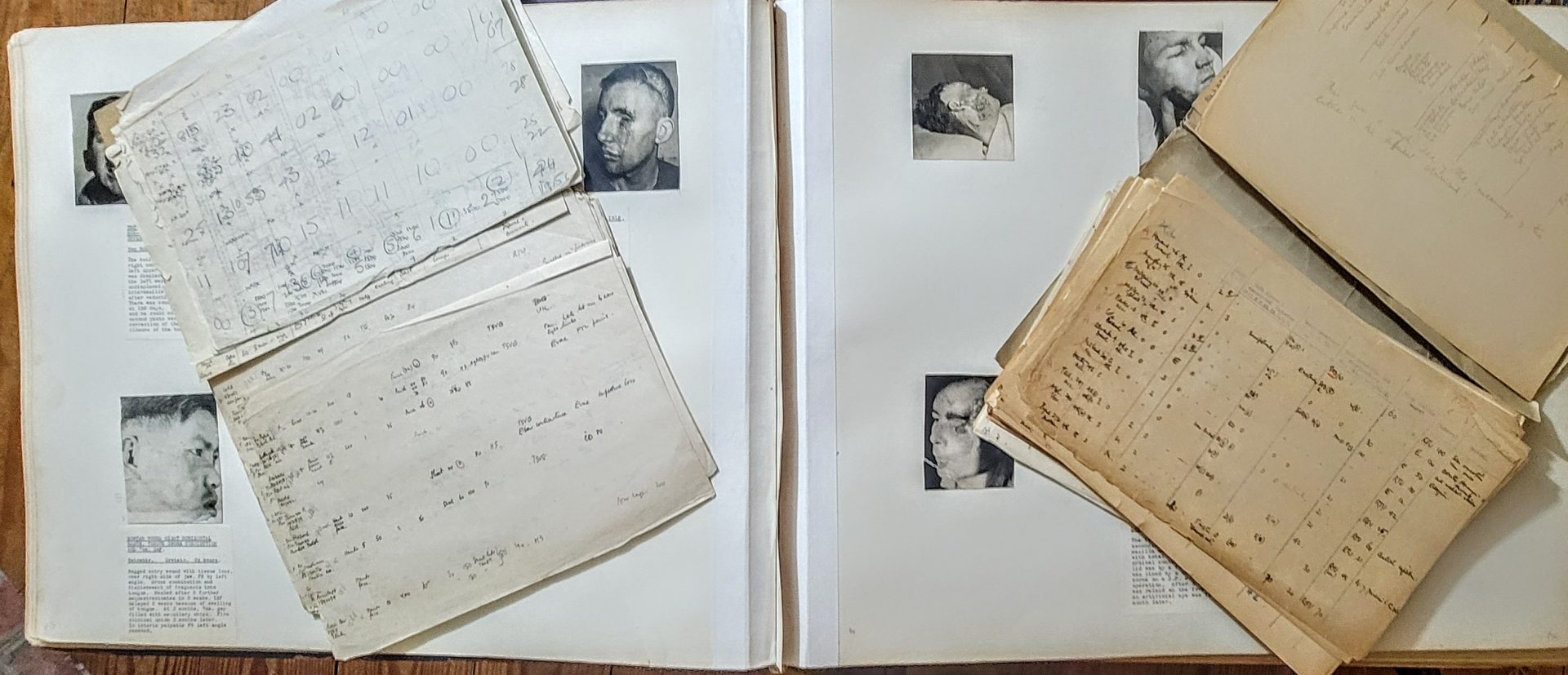

Patrick Clarkson (1911-1969)

Clarkson, a New Zealander, was evacuated from Normandy in 1940, then trained in Plastics and Hand surgery at Rooksdown House under Harold Gillies and was sent to North Africa in ’42 followed by Naples in Italy. There he served in No. IV Maxillofacial Unit as commanding Surgeon between 1942 and 1945. He meticulously kept prospective data on all his patients, and paid specific attention to how the process and timing of traumatic reconstruction, notably developing early burns eschar excision and grafting and early debridement and primary closure of facial missile wounds. He also described Poland’s syndrome in 1962, wrote Plastic Surgery of the hand in 1962 and re published Fifield’s Infections Of The Hand in 1940.

His archive contains his instruments, artifacts from his time with Gillies including oil paintings painted by that father of Plastic Surgery, with whom he shared rooms in Harley Street.

.

.

Mount Aspiring painted by Harold Gillies from the Glendu Bay lookout lake Wanaka (https://maps.app.goo.gl/xeRUSGN37ew63wnMA)

The archive also possesses items that I was lucky to have been given during my time training in London, from his old registrars. His original War data was donated by Rex Laurie in 2003, who worked with him in Cassino, Itally ’42-45. The original black and white photographs were retrieved from Roehampton Hospital, London as they were being disposed of by the old library, by Patrick Whitfield, his last Registrar who donated them in 2000. Together, these artifacts provide a very full picture of how these young surgeons faced immense surgical challenges in North Africa and Italy during WW2, having to question every surgical principle that they had been taught.

His son Gerald Clarkson married Patrick’s surgical nurse, my mother, Rachel Bowman, who had trained at St Thomas’s hospital as a Nightingale Nurse, following her own great grandfathers connections to Florence from a hundred years before.